-

in gallery

- Transit Transition >

- Remnants Of Utopia >

-

Antarctica

>

- Project Outline

- Antarctica Essay

- Reviews

- Sledge

- Toy Sledge

- Airfix Antarctic Aeroplane Hoover

- Eating Penguins

- The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner

- Toy Snowmobile

- Rat Box, Bird Island

- Rejection Letters

- The Last Roll Of Kodachrome In The World

- John Deere Gator And Specimen

- There Are No More Dogs In Antarctica

- Furthest South- J C B

- Captain Scotts Bookshelf

- Antarctic Toy Portraits

-

Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape , Escape

>

-

Offer Must End Soon

>

- Essay Jess Twyman

- Reviews

- Offer Must End Soon

- Buy My Painting!

- "Buy My Painting!" For the hard of hearing.

- "Don't Make Me Take It All Back Home With Me!"

- How We Won The War

- "Stop me and buy one!"

- 'The Cornfield'... free gift inside

- "Catalogue!"

- The Contemporary Art Scene

- Camera Crash

- "Untitled" hanging itself

- Buy My Fucking Painting!

- Absolut Ship !

- Executive Toy!

- Art Stunt Suicide Disaster

- Roll up, Roll up. Get your Art here!

- Big Country >

- All at Sea

- & Model >

- Give Me The Money

- Music and domestic appliances >

- ...on the wall...in boxes >

- Sweet Jars, glass cases on books >

- On Stage

-

Outside gallery

- Auspicious Phoenix Recycling Palace

- Covid lockdown with Boris >

- Goat Train

- washed up Car - go >

- Vanishing Point >

- Badgast Residency >

- Selfie Slot Car Racing >

- Coventry Transport Museum Residency >

- Cheap Cheap >

- A Portrait of Casper DeBoer

- Cranes

- Hessle Road Residency >

- Reisbureau Mareado >

- Windmills >

- Performance Sculptures >

- Accessible Collectible

-

publications

- Solo projects >

-

Group Projects

>

- oceans

- Photography, Curation, Criticism:

- Art in Oisterwijk 2022

- Talk to me

- & Model

- Middlesbrough Art Weekender

- Polar Record

- Translating the Street

- 1st Sino/british Cont. Art, Yentai

- Extending Ecocriticism

- The Dream Cafe

- Performance, Transport And Mobility

- shipwreck in art and literature

- Inbetween PS1, New York and Shanghai

- Odd Coupling

- Landscapes of Exploration

- IT! The Worst Magazine Ever : Poland

- Flip Shift Show Switch

- Baudrillard Now

- The Juddykes

- Dr Roberts Magic Bus

- Continental Breakfast

- Lat (living Apart Together)

- North. Amsterdam 2004

- Westwijk, Vlaardingen, De Strip

- Da Da Da Strategies Against Marketecture

- Reisburo Mareado (The Travel Brochure)

- Catalogus Mareado

- Kunst Over De Grens

- This Flat Earth

- The Uses of an Artist

- Kettles Yard Open 97

- Royal College Of Art Centenary Year

- Millennium Encyclopedia

- Press

- About / contact

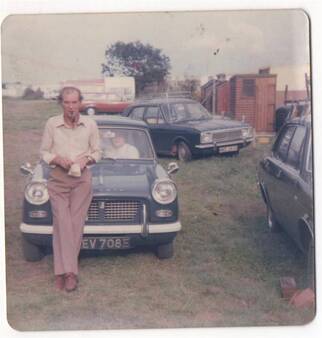

The most recent piece in the exhibition is the most overtly autobiographical. While it has many ingredients that make it a recognisable extension of the previous work, it is also a departure in several ways. Although it clearly is a vehicle, it is a mass-produced commercial car rather than one constructed by the artist. As a work it seems to speak less of 'adventures' than of the ordinariness of family life.

This Triumph Herald Estate has been part of Chris Dobrowolski's life since the day he was born in 1968. His parents decided to buy it, new from the show room, when his mother was pregnant. Designed for owner- maintenance, the car still runs today. It has been a presence, and a part of most of the events in the artist's life.

The car has been transformed into what is, in effect, a museum of its own history and the history of the artist's relationship with it. Through each window we see an enclosed display of memorabilia - documents, photographs, personally significant objects which, in this context, are loaded with nostalgia.

It's all about authentication. This is the car, that's the number plate, there are the documents and here it is today.

Maybe the piece acts as a reassurance that all the events that surrounded these remnants actually did happen. It is difficult not to see it as a kind of memorial which evokes the sadness of reviewing the pathetic objects which make up our lives. Like the larger retrospective exhibition of which it is a part this work is a kind of stock-taking. Turning out the pockets for the teacher...

I'm very nervous about this piece of work because it's quite a departure. It's not about the work involved in the making of the piece. It's about the work that I've done to keep the car running to this date.

This Triumph Herald Estate has been part of Chris Dobrowolski's life since the day he was born in 1968. His parents decided to buy it, new from the show room, when his mother was pregnant. Designed for owner- maintenance, the car still runs today. It has been a presence, and a part of most of the events in the artist's life.

The car has been transformed into what is, in effect, a museum of its own history and the history of the artist's relationship with it. Through each window we see an enclosed display of memorabilia - documents, photographs, personally significant objects which, in this context, are loaded with nostalgia.

It's all about authentication. This is the car, that's the number plate, there are the documents and here it is today.

Maybe the piece acts as a reassurance that all the events that surrounded these remnants actually did happen. It is difficult not to see it as a kind of memorial which evokes the sadness of reviewing the pathetic objects which make up our lives. Like the larger retrospective exhibition of which it is a part this work is a kind of stock-taking. Turning out the pockets for the teacher...

I'm very nervous about this piece of work because it's quite a departure. It's not about the work involved in the making of the piece. It's about the work that I've done to keep the car running to this date.

In the back window is the original bill of sale for the car alongside the artist's birth certificate and a contemporaneous advert for the Triumph Herald Estate being presented very much as a middle class family commodity with space for posh pram, thoroughbred dog, golf clubs, picnic hamper, fishing tackle. A mother is depicted carrying a baby out of the front door and down the substantial front steps of a mature home towards the waiting Estate car. The contrast with the evidence of Dobrowolski's museum is inescapable. The ironic rejection of commercial interests and the obsession with 'goods' and commodities is clear.

When I finished my three years in Hull I went home in debt to live with my parents. Dad had kept the car in the garage for me. When I looked at it the car was, like, a wreck. It had rusted away. There was a moment when he was quite adamant that I should throw it away. He was quite vocal about that. He had retired from work and was very depressed. I'd spent all that time in college going on in a hippie 'doing-it-for-real' way about 'integrity' in making vehicles, then I'm faced with the car that I've had since birth and my Dad's going to throw it away. So there was a massive dilemma there and I ended up spending my first year out of college, not making art but fixing this car. I put more time into fixing that car than it was ever going to be worth. It would have been far more practical to buy another car - plus you wouldn't have the constant fear that you were gonna crash this precious thing whenever you drive it. I spent all my days living there, getting up in the morning, going down to this lock up garage and struggling with how the car went together, not being quite sure what I was doing. I would go back home and say to my Dad, 'You know when you're greasing the front wheel hubs, do you fill the cavity or...' 'Don't f***ing depress me with that f***ing car. You are wasting your life. Go to art college and think you're something special ah. If only I had pushed it in the f***ing ditch.' This went on for a whole year and I finally got it fixed and working again and he says, 'Christopher, I want you to drive me to the club. I want all my friends to see what a beautiful car I have.'

Another window contains years of tax discs, a drawing that Dobrowolski made of the car when he was eleven years old, the original service book and handbook.

He'd had the car from new and I found the service schedule in a drawer somewhere. It had little tickets that you tear out each service and the first one had been torn out and all the others were still intact in this book. And I questioned him about that. And he said, 'Took it to bloody service station for this ten thousand, twenty f***ing thousand mile service. They put it on this ramp. Triumph Herald had special new independent suspension with a special split ramp where you go up and the wheels come out like this. They put it on the ramp. They put it through there and broke the f***ing brake pipe. Didn't tell me. I went to pick up the car. Paid for the f***ing car. Got in the f***ing car. Drove off the f***ing forecourt straight into side of f***ing Volks-Wagon Beetle. Told me I'd driven it off the premises and so they weren't f***ing liable. I never took it for f***ing service ever f***ing again.'

.....................................................

Through the rear passenger window we see a Scalextric track on which a model of the estate car runs round a record-player and an LP record cover of Abbey Road by the Beatles. The famous image of the band walking across a zebra crossing is well known for the presence of a VW Beetle parked at the kerb - visible by George Harrison's head. Here, though, the significance of the photograph lies in the fact that above Paul McCartney's head is a blue Triumph Herald Estate. It's a nice thought that the piece is actually independent of the gallery. All the moving parts in the car run off the battery. I should be able to take out the museum stuff and put it in the boot, drive wherever, set it up, lock the car and walk away. So in theory I can show wherever I want to. What I thought was funny was that you could build up quite an impressive cv out of it if you wanted to. You could drive it to the Tate, put it on a parking meter, get a photo... Anywhere from the Tate Gallery to... Where I'd really like to show it is outside my Mum's house.

Another window contains years of tax discs, a drawing that Dobrowolski made of the car when he was eleven years old, the original service book and handbook.

He'd had the car from new and I found the service schedule in a drawer somewhere. It had little tickets that you tear out each service and the first one had been torn out and all the others were still intact in this book. And I questioned him about that. And he said, 'Took it to bloody service station for this ten thousand, twenty f***ing thousand mile service. They put it on this ramp. Triumph Herald had special new independent suspension with a special split ramp where you go up and the wheels come out like this. They put it on the ramp. They put it through there and broke the f***ing brake pipe. Didn't tell me. I went to pick up the car. Paid for the f***ing car. Got in the f***ing car. Drove off the f***ing forecourt straight into side of f***ing Volks-Wagon Beetle. Told me I'd driven it off the premises and so they weren't f***ing liable. I never took it for f***ing service ever f***ing again.'

.....................................................

Through the rear passenger window we see a Scalextric track on which a model of the estate car runs round a record-player and an LP record cover of Abbey Road by the Beatles. The famous image of the band walking across a zebra crossing is well known for the presence of a VW Beetle parked at the kerb - visible by George Harrison's head. Here, though, the significance of the photograph lies in the fact that above Paul McCartney's head is a blue Triumph Herald Estate. It's a nice thought that the piece is actually independent of the gallery. All the moving parts in the car run off the battery. I should be able to take out the museum stuff and put it in the boot, drive wherever, set it up, lock the car and walk away. So in theory I can show wherever I want to. What I thought was funny was that you could build up quite an impressive cv out of it if you wanted to. You could drive it to the Tate, put it on a parking meter, get a photo... Anywhere from the Tate Gallery to... Where I'd really like to show it is outside my Mum's house.