-

in gallery

- Transit Transition >

- Remnants Of Utopia >

-

Antarctica

>

- Project Outline

- Antarctica Essay

- Reviews

- Sledge

- Toy Sledge

- Airfix Antarctic Aeroplane Hoover

- Eating Penguins

- The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner

- Toy Snowmobile

- Rat Box, Bird Island

- Rejection Letters

- The Last Roll Of Kodachrome In The World

- John Deere Gator And Specimen

- There Are No More Dogs In Antarctica

- Furthest South- J C B

- Captain Scotts Bookshelf

- Antarctic Toy Portraits

-

Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape , Escape

>

-

Offer Must End Soon

>

- Essay Jess Twyman

- Reviews

- Offer Must End Soon

- Buy My Painting!

- "Buy My Painting!" For the hard of hearing.

- "Don't Make Me Take It All Back Home With Me!"

- How We Won The War

- "Stop me and buy one!"

- 'The Cornfield'... free gift inside

- "Catalogue!"

- The Contemporary Art Scene

- Camera Crash

- "Untitled" hanging itself

- Buy My Fucking Painting!

- Absolut Ship !

- Executive Toy!

- Art Stunt Suicide Disaster

- Roll up, Roll up. Get your Art here!

- Big Country >

- All at Sea

- & Model >

- Give Me The Money

- Music and domestic appliances >

- ...on the wall...in boxes >

- Sweet Jars, glass cases on books >

- On Stage

-

Outside gallery

- Auspicious Phoenix Recycling Palace

- Covid lockdown with Boris >

- Goat Train

- washed up Car - go >

- Vanishing Point >

- Badgast Residency >

- Selfie Slot Car Racing >

- Coventry Transport Museum Residency >

- Cheap Cheap >

- A Portrait of Casper DeBoer

- Cranes

- Hessle Road Residency >

- Reisbureau Mareado >

- Windmills >

- Performance Sculptures >

- Accessible Collectible

-

publications

- Solo projects >

-

Group Projects

>

- oceans

- Photography, Curation, Criticism:

- Art in Oisterwijk 2022

- Talk to me

- & Model

- Middlesbrough Art Weekender

- Polar Record

- Translating the Street

- 1st Sino/british Cont. Art, Yentai

- Extending Ecocriticism

- The Dream Cafe

- Performance, Transport And Mobility

- shipwreck in art and literature

- Inbetween PS1, New York and Shanghai

- Odd Coupling

- Landscapes of Exploration

- IT! The Worst Magazine Ever : Poland

- Flip Shift Show Switch

- Baudrillard Now

- The Juddykes

- Dr Roberts Magic Bus

- Continental Breakfast

- Lat (living Apart Together)

- North. Amsterdam 2004

- Westwijk, Vlaardingen, De Strip

- Da Da Da Strategies Against Marketecture

- Reisburo Mareado (The Travel Brochure)

- Catalogus Mareado

- Kunst Over De Grens

- This Flat Earth

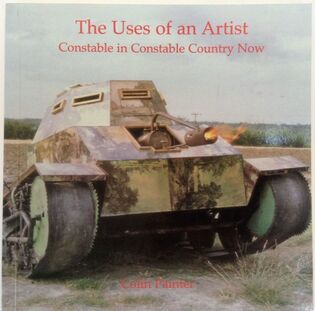

- The Uses of an Artist

- Kettles Yard Open 97

- Royal College Of Art Centenary Year

- Millennium Encyclopedia

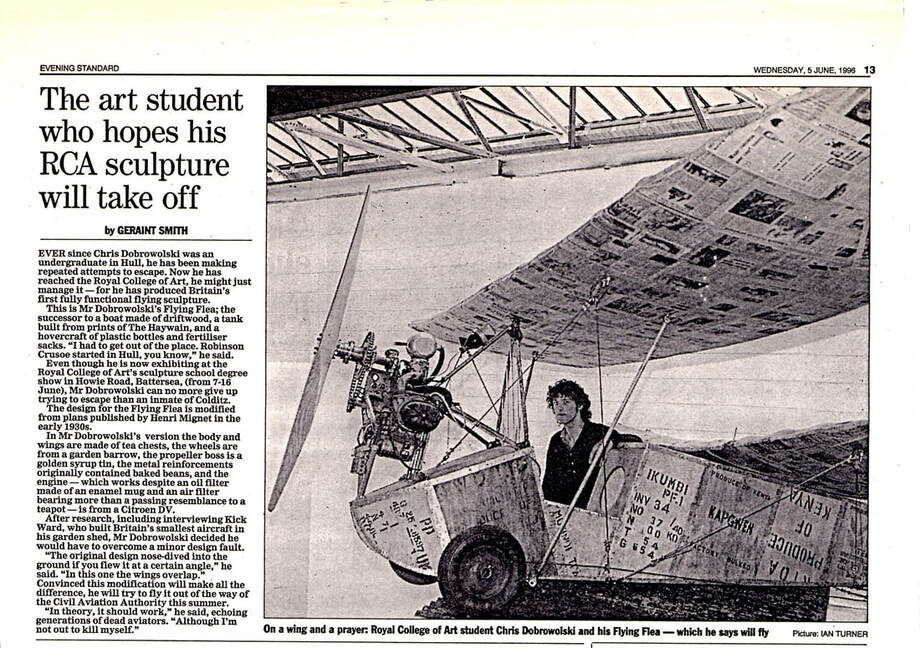

- Press

- About / contact

"Reviewing my reviews"

It's fair to say that 'Landscape Escape No.2' (the tank) 'piggy backed' its way into a couple of glossy art mags solely by virtue of it being on the front cover of 'Colin Painter's' book 'The Uses of an Artist'. In 'Frieze magazine' the tank comes out ok but the writer 'David Barret' was less kind about the book itself. At the time I thought this was an inevitability. I learnt a lot from Colin's academic ethos of 'inclusivity' but 'Frieze magazine' - arguably the ultimate 'gate keeper' to the contemporary art world of the pre internet 90's- was in essence all about being 'exclusive'. I once met a Japanese artist at a party who was on a networking trip to London. He told me that he "...only wanted to talk to artist's who had been in 'Frieze magazine!" This was just prior to the article in Frieze so we didn't chat for long.

Frieze (Issue 45- Mar.-Apr. 1999) Home is where the art is

David Barrett wonders how useful art should be

David Barrett wonders how useful art should be

Don't be thrown by the cover - the tank camouflaged with Constable reproductions is an artwork by Chris Dobrowolski, whereas most of the 'uses' of Constable in this book are rather more mun- dane. Indeed, it is mundanity which is champi- oned. For Colin Painter the term 'use' refers to the many ways in which people relate to art- works, including such diverse functions as being sites of aesthetic contemplation, models for theoretical interpretation, wedding gifts, souvenirs, decoration and so forth. A 'useful' artwork does- n't have to be trowel-shaped and good for digging the garden, but Painter wouldn't exclude such literal functionality.

The Uses of an Artist appeals for contemporary art to make itself more accessible to a wider audience. 'Not again', you might say, but this aim is far from universal - many would maintain that an artwork can be successful even if it only reaches a tiny audience. But Painter argues that since much art is funded by the taxpayer, from public galleries and collections through to the provision of art courses in schools and universities, this accessibility is key. Contemporary art, he suggests, has gnawed at the hand that feeds it for years. Taking public money, while greeting any concessions to public accessibility with righteous indignation, can only leave art in an untenable position.

The book comprises interviews with volunteers from around the Stour Valley area 'Constable Country' - concerning their personal engagement with Constable's work. Some of the respondents were artists and some were Constable enthusiasts, but mostly they were neither. All, however, owned some form of Constable reproduction, ranging from original mezzotints by Constable's engraver David Lucas, to art prints, tapestries, table mats, jugs and jigsaws. Painter explored the variety of ways in which people engaged with Constable's art in their homes and everyday lives. It's an intriguing project, if mas- sively flawed - the choice of Constable in Constable Country seems almost wilfully designed to nullify any broader significance.

The logic put forward is that Constable's work proves that high art can appeal to a more general public. Yet the problems are numerous. Constable obviously appeals in his own backyard: the pride of a local boy done good helps, as does the fact that the landscapes still exist. Further, Constable is a naturalistic, quintessentially English painter, and the volunteers find his work familiar and safe. Yet none of the interviewees are from ethnic backgrounds, immediately excluding a huge swathe of the British population. Finally, Constable's paintings are nearly 200 years old: whatever radicality they had when first produced (his so-called 'snow' effect, for example) has since been absorbed to the point of cliché.

Whatever qualities the contemporary art world sees in Constable, his originality is only appreciated through the lens of art history. If he were making such paintings today, they would have far less to recommend them. Painter makes it clear that he does not expect contemporary artists to be making works that look like Constable's, but it is too late; his argument is muddied. Perhaps a subsequent project might look at a variety of more recent artists - after all, the artist who sells the most prints at the Tate is not some traditional English landscape painter, but Mark Rothko.

Painter calls for contemporary art to explore wider avenues of distribution (for prints to be available in home decoration stores, for example - perhaps he hasn't visited Habitat). He wants artists to recognise that works have 'extra-picto- rial', anecdotal meanings, making them inseparable from daily life. He wants continuities between high art and grass-roots low-key practices. He wants art to accept that pleasure and celebration are legitimate goals. Above all, he wants artists to produce works that aim at domestic use, rather than institutional display. In themselves these are interesting possibilities, argued with intelligence, despite the book's peculiar methods and off-putting Borough Council design.

The central argument is that contemporary art has isolated itself from the general public: that art's oppositional status has been institu- tionalised (even the Chairman of the Arts Council agrees with this one). But, of course, many artists have explicitly attempted to reach a wider public. A few recent examples would be the fly- poster campaigns by Tim Noble and Sue Webster, Must Go magazine distributed on trains by Marysia Lewandowska and The Mule Newspaper, given out free for one day by street corner ven- dors across the country. There are many, many other examples. What Painter correctly points out is that few of these actually aim to provide art for the home - it is left to the major public galleries to produce affordable posters, although these tend to be reproductions of paintings rather than works specifically designed for print.

Painter makes his case clearly and in refreshingly straightforward prose; his project has many values which will hopefully lead to action. But fundamentally, it comes down to a question that Painter himself asks: 'what steps might be necessary [for contemporary art] to engage more with the priorities of people who currently do not participate in that world, and would the steps have such an adverse effect that they would be unacceptable?' Unfortunately, this is a question that Constable cannot answer.

The Uses of an Artist appeals for contemporary art to make itself more accessible to a wider audience. 'Not again', you might say, but this aim is far from universal - many would maintain that an artwork can be successful even if it only reaches a tiny audience. But Painter argues that since much art is funded by the taxpayer, from public galleries and collections through to the provision of art courses in schools and universities, this accessibility is key. Contemporary art, he suggests, has gnawed at the hand that feeds it for years. Taking public money, while greeting any concessions to public accessibility with righteous indignation, can only leave art in an untenable position.

The book comprises interviews with volunteers from around the Stour Valley area 'Constable Country' - concerning their personal engagement with Constable's work. Some of the respondents were artists and some were Constable enthusiasts, but mostly they were neither. All, however, owned some form of Constable reproduction, ranging from original mezzotints by Constable's engraver David Lucas, to art prints, tapestries, table mats, jugs and jigsaws. Painter explored the variety of ways in which people engaged with Constable's art in their homes and everyday lives. It's an intriguing project, if mas- sively flawed - the choice of Constable in Constable Country seems almost wilfully designed to nullify any broader significance.

The logic put forward is that Constable's work proves that high art can appeal to a more general public. Yet the problems are numerous. Constable obviously appeals in his own backyard: the pride of a local boy done good helps, as does the fact that the landscapes still exist. Further, Constable is a naturalistic, quintessentially English painter, and the volunteers find his work familiar and safe. Yet none of the interviewees are from ethnic backgrounds, immediately excluding a huge swathe of the British population. Finally, Constable's paintings are nearly 200 years old: whatever radicality they had when first produced (his so-called 'snow' effect, for example) has since been absorbed to the point of cliché.

Whatever qualities the contemporary art world sees in Constable, his originality is only appreciated through the lens of art history. If he were making such paintings today, they would have far less to recommend them. Painter makes it clear that he does not expect contemporary artists to be making works that look like Constable's, but it is too late; his argument is muddied. Perhaps a subsequent project might look at a variety of more recent artists - after all, the artist who sells the most prints at the Tate is not some traditional English landscape painter, but Mark Rothko.

Painter calls for contemporary art to explore wider avenues of distribution (for prints to be available in home decoration stores, for example - perhaps he hasn't visited Habitat). He wants artists to recognise that works have 'extra-picto- rial', anecdotal meanings, making them inseparable from daily life. He wants continuities between high art and grass-roots low-key practices. He wants art to accept that pleasure and celebration are legitimate goals. Above all, he wants artists to produce works that aim at domestic use, rather than institutional display. In themselves these are interesting possibilities, argued with intelligence, despite the book's peculiar methods and off-putting Borough Council design.

The central argument is that contemporary art has isolated itself from the general public: that art's oppositional status has been institu- tionalised (even the Chairman of the Arts Council agrees with this one). But, of course, many artists have explicitly attempted to reach a wider public. A few recent examples would be the fly- poster campaigns by Tim Noble and Sue Webster, Must Go magazine distributed on trains by Marysia Lewandowska and The Mule Newspaper, given out free for one day by street corner ven- dors across the country. There are many, many other examples. What Painter correctly points out is that few of these actually aim to provide art for the home - it is left to the major public galleries to produce affordable posters, although these tend to be reproductions of paintings rather than works specifically designed for print.

Painter makes his case clearly and in refreshingly straightforward prose; his project has many values which will hopefully lead to action. But fundamentally, it comes down to a question that Painter himself asks: 'what steps might be necessary [for contemporary art] to engage more with the priorities of people who currently do not participate in that world, and would the steps have such an adverse effect that they would be unacceptable?' Unfortunately, this is a question that Constable cannot answer.

The Royal Accademy Magazine (Issue 60 autumn 1998)

Local Constable by Andrew Lambirth

Colin Painter, artist and writer about art, is fascinated by the contemporary relevance of Constable. Two years ago he organised an exhibition at the National Gallery about the place occupied in ordinary people's lives by Constable's great painting 'The Cornfield'. Now he explores the way Constable still permeates his native Suffolk. As well as wall-texts and photographs, the show ranges from Constable road signs to a painting by the artist's great-great- grandson and includes Chris Dobrowolski's flame-throwing tank armoured with reproduction Constable paintings. Thought- provoking and unusual.

The Guardian- June 2005

Art Fortnight London - click this button here

Art Fortnight London - click this button here

Art Fortnight London, Metro newspaper 2005- only '3 stars'... for the whole show - not just me.

The Volksrant (Dutch national paper) 'LAT' 'Living Apart Together', Oda Park, Venray, 2004

...Britain's Chris Dobrowolski's famous tank is more reminiscent of the well-built soapbox of boys playing soldiers than of dangerous weapons of war.

...Britain's Chris Dobrowolski's famous tank is more reminiscent of the well-built soapbox of boys playing soldiers than of dangerous weapons of war.

A note from me: For some reason 'The Volksrant' always seems to state the obvious and manage to sound cendescending at the same time.

Click this button for the

'Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape, Escape' page

'Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape, Escape' page