-

in gallery

- Transit Transition >

- Remnants Of Utopia >

-

Antarctica

>

- Project Outline

- Antarctica Essay

- Reviews

- Sledge

- Toy Sledge

- Airfix Antarctic Aeroplane Hoover

- Eating Penguins

- The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner

- Toy Snowmobile

- Rat Box, Bird Island

- Rejection Letters

- The Last Roll Of Kodachrome In The World

- John Deere Gator And Specimen

- There Are No More Dogs In Antarctica

- Furthest South- J C B

- Captain Scotts Bookshelf

- Antarctic Toy Portraits

-

Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape , Escape

>

-

Offer Must End Soon

>

- Essay Jess Twyman

- Reviews

- Offer Must End Soon

- Buy My Painting!

- "Buy My Painting!" For the hard of hearing.

- "Don't Make Me Take It All Back Home With Me!"

- How We Won The War

- "Stop me and buy one!"

- 'The Cornfield'... free gift inside

- "Catalogue!"

- The Contemporary Art Scene

- Camera Crash

- "Untitled" hanging itself

- Buy My Fucking Painting!

- Absolut Ship !

- Executive Toy!

- Art Stunt Suicide Disaster

- Roll up, Roll up. Get your Art here!

- Big Country >

- All at Sea

- & Model >

- Give Me The Money

- Music and domestic appliances >

- ...on the wall...in boxes >

- Sweet Jars, glass cases on books >

- On Stage

-

Outside gallery

- Auspicious Phoenix Recycling Palace

- Covid lockdown with Boris >

- Goat Train

- washed up Car - go >

- Vanishing Point >

- Badgast Residency >

- Selfie Slot Car Racing >

- Coventry Transport Museum Residency >

- Cheap Cheap >

- A Portrait of Casper DeBoer

- Cranes

- Hessle Road Residency >

- Reisbureau Mareado >

- Windmills >

- Performance Sculptures >

- Accessible Collectible

-

publications

- Solo projects >

-

Group Projects

>

- oceans

- Photography, Curation, Criticism:

- Art in Oisterwijk 2022

- Talk to me

- & Model

- Middlesbrough Art Weekender

- Polar Record

- Translating the Street

- 1st Sino/british Cont. Art, Yentai

- Extending Ecocriticism

- The Dream Cafe

- Performance, Transport And Mobility

- shipwreck in art and literature

- Inbetween PS1, New York and Shanghai

- Odd Coupling

- Landscapes of Exploration

- IT! The Worst Magazine Ever : Poland

- Flip Shift Show Switch

- Baudrillard Now

- The Juddykes

- Dr Roberts Magic Bus

- Continental Breakfast

- Lat (living Apart Together)

- North. Amsterdam 2004

- Westwijk, Vlaardingen, De Strip

- Da Da Da Strategies Against Marketecture

- Reisburo Mareado (The Travel Brochure)

- Catalogus Mareado

- Kunst Over De Grens

- This Flat Earth

- The Uses of an Artist

- Kettles Yard Open 97

- Royal College Of Art Centenary Year

- Millennium Encyclopedia

- Press

- About / contact

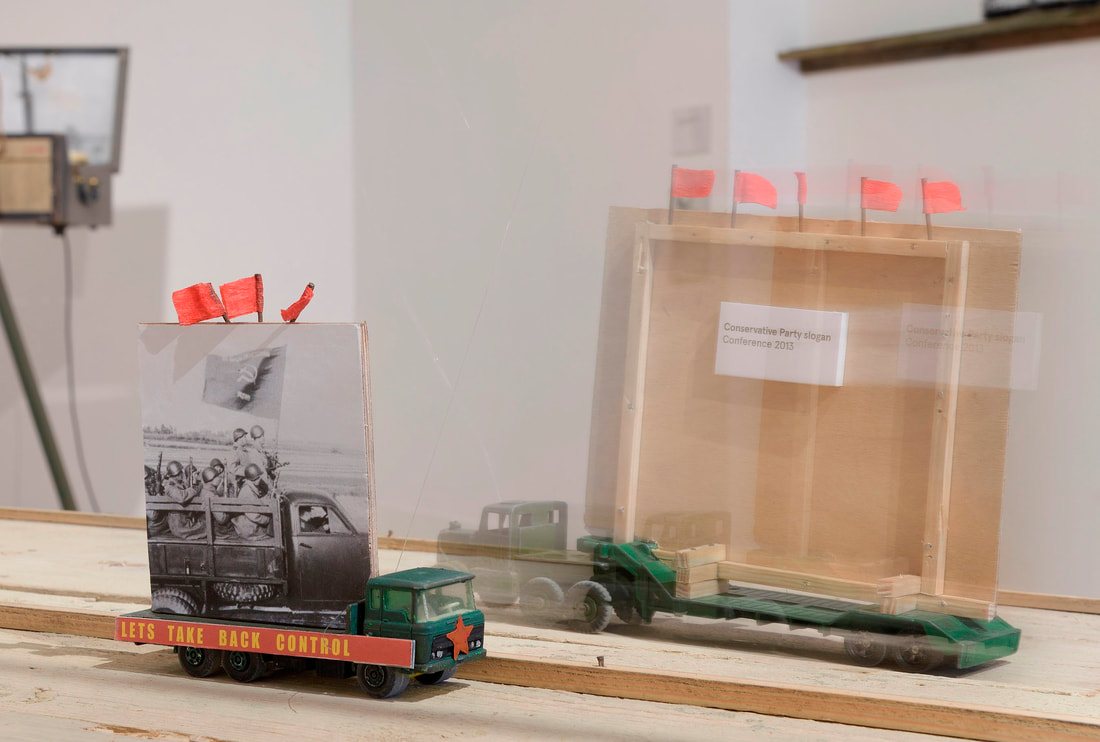

Photo Doug Atfield

Photo Doug Atfield

The mechanics of this piece came from an earlier unresolved work made on a residency in Hessle Road, Hull 2008. Totally re-built for the exhibition in Art Exchange I was invited to make it so that it coincided with the centenary of the Russian revolution in November 2017.

The Russian revolution is a contentious subject. However the nature of a centenary not only re-visits the events of the time but also the 100 year arc of history since; highlighting what's happened historically to the present day.

When I was growing up in the 1970's and 80's during the cold war, the Soviet Union was the enemy, an external threat. It was difficult at the time to find anything positive about it. However, if we accept that 19th century British social reforms came about to quell the sort of unrest that led to the French revolution, then 20th century social reforms might equally be a means to pacify social discontent in the 20th century after the Russian revolution. In this context, the people who probably benefited the most from the Russian revolution were the proletariat that lived 'outside' the Communist system in the West.

To quote the US president J.F. Kennedy.

"Those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable".

Whether the post war political consensus had run its course or was prematurely killed by Thatcherism is debatable. However it is interesting to note that many of the social reforms and general redistribution of wealth that had occurred in the 20th century have slowly evaporated since the fall of communism in the early 90's.

These toy Communist parade trucks use British 'right of centre' political election campaign slogans. My intention was to emphasise the correlation between the 'threat' of the Russian revolution and the domestic political world I have lived in all my life.

The Russian revolution is a contentious subject. However the nature of a centenary not only re-visits the events of the time but also the 100 year arc of history since; highlighting what's happened historically to the present day.

When I was growing up in the 1970's and 80's during the cold war, the Soviet Union was the enemy, an external threat. It was difficult at the time to find anything positive about it. However, if we accept that 19th century British social reforms came about to quell the sort of unrest that led to the French revolution, then 20th century social reforms might equally be a means to pacify social discontent in the 20th century after the Russian revolution. In this context, the people who probably benefited the most from the Russian revolution were the proletariat that lived 'outside' the Communist system in the West.

To quote the US president J.F. Kennedy.

"Those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable".

Whether the post war political consensus had run its course or was prematurely killed by Thatcherism is debatable. However it is interesting to note that many of the social reforms and general redistribution of wealth that had occurred in the 20th century have slowly evaporated since the fall of communism in the early 90's.

These toy Communist parade trucks use British 'right of centre' political election campaign slogans. My intention was to emphasise the correlation between the 'threat' of the Russian revolution and the domestic political world I have lived in all my life.

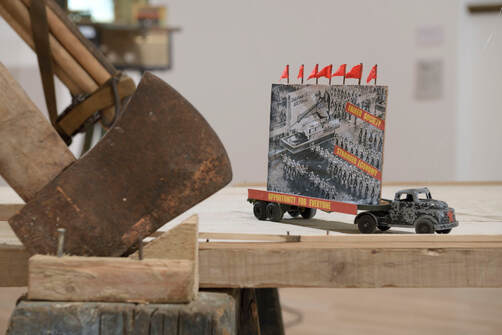

Photo Doug Atfield

Photo Doug Atfield

I can remember seeing segments of the Moscow Mayday parades as they were briefly televised on the news during the 70's and 80's. 'Mayday parade' is possibly a technically incorrect title for this piece. November revolution parade would probably be more appropriate. For me and I imagine others growing up in the UK at the time, all the parades that were in Moscow's red square during the communist era looked pretty similar. 'The Mayday parade' being the easiest one to remember, obviously stuck in the mind hence it's been used here as the title.

Being the enemy during the cold war, anything Russian or communist was always taken as a 'bad thing' and this included the May day parade. In the west we saw them as some kind of 'forced fun' and a manifestation of the totalitarian state. All the statements and proud boasts written on the parade trucks were either pointless or complete fabrications designed to prop up a failed system. At one time the title for this work was going to be 'The Bullshit Parade'.

The materials used to make this piece were tools and other workman like elements. The long table suggested a work bench. All the stool legs underneath were in fact made by my father. He was a carpenter and these were his saw horses. He also used to repair his own boots. His cobbler's lasts are incorporated in the work holding the bench in place between the floor and roof of the gallery whilst also pinning a red star to the ceiling.

Being the enemy during the cold war, anything Russian or communist was always taken as a 'bad thing' and this included the May day parade. In the west we saw them as some kind of 'forced fun' and a manifestation of the totalitarian state. All the statements and proud boasts written on the parade trucks were either pointless or complete fabrications designed to prop up a failed system. At one time the title for this work was going to be 'The Bullshit Parade'.

The materials used to make this piece were tools and other workman like elements. The long table suggested a work bench. All the stool legs underneath were in fact made by my father. He was a carpenter and these were his saw horses. He also used to repair his own boots. His cobbler's lasts are incorporated in the work holding the bench in place between the floor and roof of the gallery whilst also pinning a red star to the ceiling.

Photo Doug Atfield

Photo Doug Atfield

Each piece in the show had a text pamphlet accompanying it. These were nailed onto the wall next to the work and visitors were encouraged to tear them off and take them away. Although visually reminiscent of a plane political pamphlet of the turn of the century; instead of being an impersonal political statement each text tells a personal story that informs the work.

The text for 'Miniature Austerity Mayday Parade' pamphlet is written out below.

Each lorry has been made into a simplified parade float, reminiscent of the parades in Moscow’s Red Square during Russia’s Communist era. Instead of the usual celebratory Communist messages each ones bears a slogan from various right- of- centre political parties from the post war period to the present day. The lorries used are similar to ones I would have played with when I was at school in the 1970’s.

At my bog standard comprehensive school, each morning we gathered in the assembly hall to sing a hymn and listen to that day’s presentation from the headmaster. Overall, the message was the same; a moral lesson or virtuous tale about being fair and the evils of the seven deadly sins. In this way, slowly over time, we were indoctrinated into being kind to others and the importance of the common good. This happened right up until the mid-1980’s at which point we were thrust out into Margaret Thatcher’s Britain and quickly realised the world wasn’t quite the same as the one depicted in school assembly. I managed to stave off entering the real world for a bit longer by going to Art College.

My father was a carpenter and when I first told him I was going to art college he took me to the window gestured to his shed full of tools at the bottom of the garden and said dramatically, “…but I wanted you to be a carpenter like me- I have a shed full of tools there and I wanted to give them to you when I died.”

The text for 'Miniature Austerity Mayday Parade' pamphlet is written out below.

Each lorry has been made into a simplified parade float, reminiscent of the parades in Moscow’s Red Square during Russia’s Communist era. Instead of the usual celebratory Communist messages each ones bears a slogan from various right- of- centre political parties from the post war period to the present day. The lorries used are similar to ones I would have played with when I was at school in the 1970’s.

At my bog standard comprehensive school, each morning we gathered in the assembly hall to sing a hymn and listen to that day’s presentation from the headmaster. Overall, the message was the same; a moral lesson or virtuous tale about being fair and the evils of the seven deadly sins. In this way, slowly over time, we were indoctrinated into being kind to others and the importance of the common good. This happened right up until the mid-1980’s at which point we were thrust out into Margaret Thatcher’s Britain and quickly realised the world wasn’t quite the same as the one depicted in school assembly. I managed to stave off entering the real world for a bit longer by going to Art College.

My father was a carpenter and when I first told him I was going to art college he took me to the window gestured to his shed full of tools at the bottom of the garden and said dramatically, “…but I wanted you to be a carpenter like me- I have a shed full of tools there and I wanted to give them to you when I died.”

Photo Doug Atfield

Photo Doug Atfield

As part of the preparation for starting my art course the college sent a letter that included an inventory of tools that I was required to bring with me. It was a basic list which mentioned, amongst other things, a hammer. Dad went to the shed and from a selection of ten, sent me away to Art College with one in particular. “This was my first ever hammer” he said proudly.

For years I thought he must have bought it sometime in the late 1940’s when he came to England after world war two and got his first job on a building site. It turns out he bought it a lot later. For the first few years he had found it easier to use the flat, back end of an axe. Having spent a year and a half doing hard labour in Siberia, mainly chopping down trees, an axe was what he was used to.

For years I thought he must have bought it sometime in the late 1940’s when he came to England after world war two and got his first job on a building site. It turns out he bought it a lot later. For the first few years he had found it easier to use the flat, back end of an axe. Having spent a year and a half doing hard labour in Siberia, mainly chopping down trees, an axe was what he was used to.

Photo Doug Atfield

Photo Doug Atfield

A year and a half in Siberia, plus another 4 years in the army during the war gave my father a healthy distrust of authority. He didnt like his manager on one of the building sites he worked on because he acted superior. He noticed that he kept looking out of his window to make sure my father was doing his job properly. Eventually my father lost his temper, and stormed into the office and told him to stop checking up on him. To my father’s surprise the manager was very apologetic and backed down immediately. As he left he wondered why the manager had been so amicable, until he noticed he had stormed into the office still carrying his axe.