-

in gallery

- Transit Transition >

- Remnants Of Utopia >

-

Antarctica

>

- Project Outline

- Antarctica Essay

- Reviews

- Sledge

- Toy Sledge

- Airfix Antarctic Aeroplane Hoover

- Eating Penguins

- The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner

- Toy Snowmobile

- Rat Box, Bird Island

- Rejection Letters

- The Last Roll Of Kodachrome In The World

- John Deere Gator And Specimen

- There Are No More Dogs In Antarctica

- Furthest South- J C B

- Captain Scotts Bookshelf

- Antarctic Toy Portraits

-

Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape , Escape

>

-

Offer Must End Soon

>

- Essay Jess Twyman

- Reviews

- Offer Must End Soon

- Buy My Painting!

- "Buy My Painting!" For the hard of hearing.

- "Don't Make Me Take It All Back Home With Me!"

- How We Won The War

- "Stop me and buy one!"

- 'The Cornfield'... free gift inside

- "Catalogue!"

- The Contemporary Art Scene

- Camera Crash

- "Untitled" hanging itself

- Buy My Fucking Painting!

- Absolut Ship !

- Executive Toy!

- Art Stunt Suicide Disaster

- Roll up, Roll up. Get your Art here!

- Big Country >

- All at Sea

- & Model >

- Give Me The Money

- Music and domestic appliances >

- ...on the wall...in boxes >

- Sweet Jars, glass cases on books >

- On Stage

-

Outside gallery

- Auspicious Phoenix Recycling Palace

- Covid lockdown with Boris >

- Goat Train

- washed up Car - go >

- Vanishing Point >

- Badgast Residency >

- Selfie Slot Car Racing >

- Coventry Transport Museum Residency >

- Cheap Cheap >

- A Portrait of Casper DeBoer

- Cranes

- Hessle Road Residency >

- Reisbureau Mareado >

- Windmills >

- Performance Sculptures >

- Accessible Collectible

-

publications

- Solo projects >

-

Group Projects

>

- oceans

- Photography, Curation, Criticism:

- Art in Oisterwijk 2022

- Talk to me

- & Model

- Middlesbrough Art Weekender

- Polar Record

- Translating the Street

- 1st Sino/british Cont. Art, Yentai

- Extending Ecocriticism

- The Dream Cafe

- Performance, Transport And Mobility

- shipwreck in art and literature

- Inbetween PS1, New York and Shanghai

- Odd Coupling

- Landscapes of Exploration

- IT! The Worst Magazine Ever : Poland

- Flip Shift Show Switch

- Baudrillard Now

- The Juddykes

- Dr Roberts Magic Bus

- Continental Breakfast

- Lat (living Apart Together)

- North. Amsterdam 2004

- Westwijk, Vlaardingen, De Strip

- Da Da Da Strategies Against Marketecture

- Reisburo Mareado (The Travel Brochure)

- Catalogus Mareado

- Kunst Over De Grens

- This Flat Earth

- The Uses of an Artist

- Kettles Yard Open 97

- Royal College Of Art Centenary Year

- Millennium Encyclopedia

- Press

- About / contact

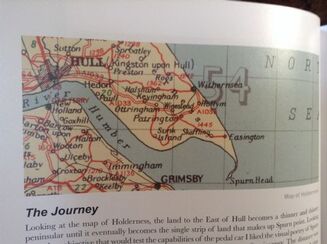

THE JOURNEY

Looking at the map of Holderness, the land to the East of Hull becomes a thinner and thinner peninsular until it eventually becomes the single strip of land that makes up Spurn point. Looking for a clear objective that would test the capabilities of the pedal car I liked the visual poetry of Spurn point. It was the very end of the land so I made this objective my first journey. The distance was about thirty miles and I estimated it would take us about a day to get there and leave enough time to put up a tent and come back the next day.

Before I describe the pedal car journey, I need to elaborate more on the context it was built in, namely Art College. The art education I had was called a ‘fine art’ degree. In fairness, this definition doesn’t really describe what happened in our department. Years later when I try to describe to the uninitiated an accurate picture of what we did I find the term ‘visual philosophy’ probably describes it best. We were encouraged to question the materials we used and to analyse the methods we used to manipulate them. We often found ourselves in an intellectual blind alley where we would revel in the grey area between definitions and quality. My favourite illustration of this is a hypothetical group tutorial I could have had whilst I was a student.

The format of the art college group tutorial usually consists of all the students from the tutorial group taking it in turns to stand around each other’s work whilst trying to think of something clever or helpful to say. Imagine everyone is looking at a three dimensional object that is quite clearly sculptural but has paint applied to it that is quite clearly painterly. Someone in the group who likes the sound of their own voice that day says ‘Sculptural yet painterly, is it a painting or is it a sculpture? It’s a grey area. Very interesting.’

Looking at the map of Holderness, the land to the East of Hull becomes a thinner and thinner peninsular until it eventually becomes the single strip of land that makes up Spurn point. Looking for a clear objective that would test the capabilities of the pedal car I liked the visual poetry of Spurn point. It was the very end of the land so I made this objective my first journey. The distance was about thirty miles and I estimated it would take us about a day to get there and leave enough time to put up a tent and come back the next day.

Before I describe the pedal car journey, I need to elaborate more on the context it was built in, namely Art College. The art education I had was called a ‘fine art’ degree. In fairness, this definition doesn’t really describe what happened in our department. Years later when I try to describe to the uninitiated an accurate picture of what we did I find the term ‘visual philosophy’ probably describes it best. We were encouraged to question the materials we used and to analyse the methods we used to manipulate them. We often found ourselves in an intellectual blind alley where we would revel in the grey area between definitions and quality. My favourite illustration of this is a hypothetical group tutorial I could have had whilst I was a student.

The format of the art college group tutorial usually consists of all the students from the tutorial group taking it in turns to stand around each other’s work whilst trying to think of something clever or helpful to say. Imagine everyone is looking at a three dimensional object that is quite clearly sculptural but has paint applied to it that is quite clearly painterly. Someone in the group who likes the sound of their own voice that day says ‘Sculptural yet painterly, is it a painting or is it a sculpture? It’s a grey area. Very interesting.’

Imagine now that the sculpture-painting was photographed and the tutorial group is looking at the photograph. The image seems to be of more value than the subject. The leader of the tutorial group puts forward the case:

‘The image seems to be of more artistic merit than the actual sculpture/ painting. You should show the photograph instead of the object, it’s much better. Is this image now more than just documentation,? And have we elevated it to the status of ‘art’ thus reducing the real thing to merely a prop for the photo..? Again, very interesting… it’s a grey area.’

I have been a teacher so I have experienced this situation from both sides. Sometimes I have had to lead a tutorial and found myself looking at a construction that stands about four inches from the floor, made thoughtlessly from chicken wire and Sellotape. My job as the tutor is to find something positive to say, even if I suspect the student wasn’t trying very hard. While I’m trying to find a diplomatic way of saying ‘this is rubbish’, I’m struck by the demeanour of the student and I’m tempted to say:

‘Yes, this is shit. But as I look at you, you are a kind of half-arsed slacker of a student and in some ways this ‘shit’ could actually be a true intellectual representation of your very soul and being. In those terms this ‘shit’ is actually quite good, hmmm… it’s a grey area.’

The antithesis of this culture is the mental approach needed by the police force. To make quick, important decisions there must be no ambiguity and no vagueness. No room for grey areas. It was on the A1033 driving the pedal car from Hull into Holderness that these two approaches met. As Eddie and I left Hull we saw a police car but, to our amazement, we shook it off

‘The image seems to be of more artistic merit than the actual sculpture/ painting. You should show the photograph instead of the object, it’s much better. Is this image now more than just documentation,? And have we elevated it to the status of ‘art’ thus reducing the real thing to merely a prop for the photo..? Again, very interesting… it’s a grey area.’

I have been a teacher so I have experienced this situation from both sides. Sometimes I have had to lead a tutorial and found myself looking at a construction that stands about four inches from the floor, made thoughtlessly from chicken wire and Sellotape. My job as the tutor is to find something positive to say, even if I suspect the student wasn’t trying very hard. While I’m trying to find a diplomatic way of saying ‘this is rubbish’, I’m struck by the demeanour of the student and I’m tempted to say:

‘Yes, this is shit. But as I look at you, you are a kind of half-arsed slacker of a student and in some ways this ‘shit’ could actually be a true intellectual representation of your very soul and being. In those terms this ‘shit’ is actually quite good, hmmm… it’s a grey area.’

The antithesis of this culture is the mental approach needed by the police force. To make quick, important decisions there must be no ambiguity and no vagueness. No room for grey areas. It was on the A1033 driving the pedal car from Hull into Holderness that these two approaches met. As Eddie and I left Hull we saw a police car but, to our amazement, we shook it off

Later, however, as we pedalled through the countryside, we passed a police van in a layby. This is how I imagine the policeman’s thought process developed:

The car passes him and he can see that, although slightly odd, it does look like a car. Then he takes in our legs going up and down and recognises this as motion normally associated with riding a bicycle. This is how it computes:

‘Not a car – not a bicycle = grey area = must be illegal!

This thought process obviously needs to happen quite quickly and he has already pulled us over before he has worked out why it is illegal. He is struggling to find a legal phrase to justify his action. When this phrase failed to materialise, he comes up with: ‘No, no, I’m sorry, but you are not… serious.’

Mindful of the fact that I had already spent two years having to justify my actions at art college as sincerely and philosophically as possible I instinctively set about stating how genuine I was, even to extent of explaining all about my ‘inner need’ and exactly ‘how’ serious I was. He wasn’t interested. I felt confident that I was OK legally as well because I’m pretty sure it doesn’t say in the Highway Code ‘you must be serious at all times on the highway’. It wasn’t long before another police car stopped, this time it was a plain-clothed policeman in an unmarked car. They conferred, then did ‘good cop bad cop’ on me. The first policeman (bad cop) was still trying to find words that best suited my traffic violation and came up with another nothing word that he picked out of the ether.

‘Reckless! That’s what you are, reckless!’

I couldn’t think of a less appropriate word. It was a giant, two-seater pedal car with a maximum speed of 10 miles per hour. Minutes earlier we had been overtaken by a milk float.

The car passes him and he can see that, although slightly odd, it does look like a car. Then he takes in our legs going up and down and recognises this as motion normally associated with riding a bicycle. This is how it computes:

‘Not a car – not a bicycle = grey area = must be illegal!

This thought process obviously needs to happen quite quickly and he has already pulled us over before he has worked out why it is illegal. He is struggling to find a legal phrase to justify his action. When this phrase failed to materialise, he comes up with: ‘No, no, I’m sorry, but you are not… serious.’

Mindful of the fact that I had already spent two years having to justify my actions at art college as sincerely and philosophically as possible I instinctively set about stating how genuine I was, even to extent of explaining all about my ‘inner need’ and exactly ‘how’ serious I was. He wasn’t interested. I felt confident that I was OK legally as well because I’m pretty sure it doesn’t say in the Highway Code ‘you must be serious at all times on the highway’. It wasn’t long before another police car stopped, this time it was a plain-clothed policeman in an unmarked car. They conferred, then did ‘good cop bad cop’ on me. The first policeman (bad cop) was still trying to find words that best suited my traffic violation and came up with another nothing word that he picked out of the ether.

‘Reckless! That’s what you are, reckless!’

I couldn’t think of a less appropriate word. It was a giant, two-seater pedal car with a maximum speed of 10 miles per hour. Minutes earlier we had been overtaken by a milk float.

ON THE BLANK CANVAS (ANTARCTICA)

The next day we drove two very powerful skidoos back up the mountain to the sledge ready for our trip. Skidoos and sledges were all joined together by the 30 metre rope and we set off across the flag line. Little red and black flags on bamboo sticks are everywhere around the base. The black ones usually mark a path or road. The red ones are for danger and usually mean there is imminent threat of a crevasse. Whilst camping they are also used to mark the spot where everyone is expected to urinate so there is less danger of digging up toilet snow to melt for drinking water. They serve as a constant reminder that you are within an area that has been tested, checked and sanitised. The flag line is the point on the mountain where the flags end and untrained people like me are not usually allowed to cross.

Vivid blue patches of sky contrasted sharply with brooding clouds but it was the way these clouds interacted with the mountains that made the landscape spectacular that day. Sometimes they hid the peaks but, at other times, the peaks were exposed as the clouds appeared to tumble down the mountainside and along the valley floor towards us. The dry Antarctic conditions had frozen the moisture in the air and altered my perception of distance. Snow covered peaks were hit by the sun which made them stick out – they felt within touching distance. Through gaps between the mountains we could see down to the sea, speckled with small blocks of ice. Beyond was the Antarctic mainland in the dreamlike distance. Occasionally I gave a sharp tug on my brake to signal Ferg to stop so that I could take it all in.

The next day we drove two very powerful skidoos back up the mountain to the sledge ready for our trip. Skidoos and sledges were all joined together by the 30 metre rope and we set off across the flag line. Little red and black flags on bamboo sticks are everywhere around the base. The black ones usually mark a path or road. The red ones are for danger and usually mean there is imminent threat of a crevasse. Whilst camping they are also used to mark the spot where everyone is expected to urinate so there is less danger of digging up toilet snow to melt for drinking water. They serve as a constant reminder that you are within an area that has been tested, checked and sanitised. The flag line is the point on the mountain where the flags end and untrained people like me are not usually allowed to cross.

Vivid blue patches of sky contrasted sharply with brooding clouds but it was the way these clouds interacted with the mountains that made the landscape spectacular that day. Sometimes they hid the peaks but, at other times, the peaks were exposed as the clouds appeared to tumble down the mountainside and along the valley floor towards us. The dry Antarctic conditions had frozen the moisture in the air and altered my perception of distance. Snow covered peaks were hit by the sun which made them stick out – they felt within touching distance. Through gaps between the mountains we could see down to the sea, speckled with small blocks of ice. Beyond was the Antarctic mainland in the dreamlike distance. Occasionally I gave a sharp tug on my brake to signal Ferg to stop so that I could take it all in.