-

in gallery

- Transit Transition >

- Remnants Of Utopia >

-

Antarctica

>

- Project Outline

- Antarctica Essay

- Reviews

- Sledge

- Toy Sledge

- Airfix Antarctic Aeroplane Hoover

- Eating Penguins

- The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner

- Toy Snowmobile

- Rat Box, Bird Island

- Rejection Letters

- The Last Roll Of Kodachrome In The World

- John Deere Gator And Specimen

- There Are No More Dogs In Antarctica

- Furthest South- J C B

- Captain Scotts Bookshelf

- Antarctic Toy Portraits

-

Landscape, Seascape, Skyscape , Escape

>

-

Offer Must End Soon

>

- Essay Jess Twyman

- Reviews

- Offer Must End Soon

- Buy My Painting!

- "Buy My Painting!" For the hard of hearing.

- "Don't Make Me Take It All Back Home With Me!"

- How We Won The War

- "Stop me and buy one!"

- 'The Cornfield'... free gift inside

- "Catalogue!"

- The Contemporary Art Scene

- Camera Crash

- "Untitled" hanging itself

- Buy My Fucking Painting!

- Absolut Ship !

- Executive Toy!

- Art Stunt Suicide Disaster

- Roll up, Roll up. Get your Art here!

- Big Country >

- All at Sea

- & Model >

- Give Me The Money

- Music and domestic appliances >

- ...on the wall...in boxes >

- Sweet Jars, glass cases on books >

- On Stage

-

Outside gallery

- Auspicious Phoenix Recycling Palace

- Covid lockdown with Boris >

- Goat Train

- washed up Car - go >

- Vanishing Point >

- Badgast Residency >

- Selfie Slot Car Racing >

- Coventry Transport Museum Residency >

- Cheap Cheap >

- A Portrait of Casper DeBoer

- Cranes

- Hessle Road Residency >

- Reisbureau Mareado >

- Windmills >

- Performance Sculptures >

- Accessible Collectible

-

publications

- Solo projects >

-

Group Projects

>

- oceans

- Photography, Curation, Criticism:

- Art in Oisterwijk 2022

- Talk to me

- & Model

- Middlesbrough Art Weekender

- Polar Record

- Translating the Street

- 1st Sino/british Cont. Art, Yentai

- Extending Ecocriticism

- The Dream Cafe

- Performance, Transport And Mobility

- shipwreck in art and literature

- Inbetween PS1, New York and Shanghai

- Odd Coupling

- Landscapes of Exploration

- IT! The Worst Magazine Ever : Poland

- Flip Shift Show Switch

- Baudrillard Now

- The Juddykes

- Dr Roberts Magic Bus

- Continental Breakfast

- Lat (living Apart Together)

- North. Amsterdam 2004

- Westwijk, Vlaardingen, De Strip

- Da Da Da Strategies Against Marketecture

- Reisburo Mareado (The Travel Brochure)

- Catalogus Mareado

- Kunst Over De Grens

- This Flat Earth

- The Uses of an Artist

- Kettles Yard Open 97

- Royal College Of Art Centenary Year

- Millennium Encyclopedia

- Press

- About / contact

Antarctica Starts Here: The Restless Travels of Chris Dobrowolski

by

Matthew Bowman

Although numerous countries are represented in Antarctica, whether through scientific research carried out there or geopolitically as signatories of the Antarctica Treaty, its harsh climate and small transitory population means that it’s about as far from the artworld—which continues to grow internationally, as attested by the proliferation of biennales and art fairs—as one can imagine.

by

Matthew Bowman

Although numerous countries are represented in Antarctica, whether through scientific research carried out there or geopolitically as signatories of the Antarctica Treaty, its harsh climate and small transitory population means that it’s about as far from the artworld—which continues to grow internationally, as attested by the proliferation of biennales and art fairs—as one can imagine.

Melon huts at Sky Blu. sledge food boxes in foreground

Melon huts at Sky Blu. sledge food boxes in foreground

It’s thoroughly appropriate, then, that the artist Chris Dobrowolski spent just over three months in that region as part of the British Antarctic Survey’s (BAS) Artists and Writers Programme, for much of Dobrowolski’s career has been characterized by a desire to distance himself from the artworld and especially from its commercially-driven manifestations. To be sure, one could argue that this distance remains limited insofar as to be identifiable as art his works must participate in the histories, logics, and institutions that constitute the artworld. But the artworld is essentially heterogeneous, thereby hinting that one can find better—fairer and more ethical—ways of inhabiting and remodelling it

Landscape Escape No.2, (tank) at Flatford mill

Landscape Escape No.2, (tank) at Flatford mill

This desire for distance has taken the form of a series of functioning vehicles made from unlikely recycled materials that both refer to the artworld and attempt escape velocity from it. For instance, his art college studies culminated with the construction of a pedal car which he used to drive away from Hull. Subsequent to that, he has made a hovercraft from bottles washed up on the shores of the River Humber; a tank from lawnmower engines and prints of John Constable’s celebrated The Hay Wain; and has even attempted to achieve flight through making his own plane based on a book detailing how to make your own “flying flea” aircraft. Although these vehicle-works ultimately spend time in the gallery, the reason underlying their construction has more to do with them actually being used as vehicles by the artist than with the beholder’s contemplation of these vehicles as unusual constructions. This gives his artistic practice a rather playful quixotic tenor, which is amplified by the fact that some of the materials used to produce his vehicles are somewhat unconventional and indicate a sensibility of bricolage.

Sledge loaded with food boxes.

Sledge loaded with food boxes.

For his residency in Antarctica, Dobrowolski built a 12-foot sledge from gilded picture frames and based upon the simple but effective “Nansen” design. Though the original pictures have been removed, this unusual use of these frames recalls Marcel Duchamp’s idea of using “a Rembrandt as an ironing board” insofar as art-related objects are reconfigured as practical items or, in this specific case, as transport. Because the frames are gold and strikingly ornamental, they connote “artworldness”—albeit the artworld at an earlier stage of historical development (despite structural transformations, however, painting remains one of the most reliable commodity items marketed by the artworld). Interestingly, and actually unknown to Dobrowolski when he conceived the frame-sledge, workers living in the Antarctic occasionally fashion picture frames from broken Nansen sledges. Despite the fact that he was unaware of this until he arrived in Antarctica, the loop or oscillation made from sledge-to-frame-to-sledge is deeply and structurally congruent with Dobrowolski’s practice: in his earlier works, for instance, washed-up bottles became his hovercraft and then afterwards returned to the River Humber, and his tank was photographed outside Willy Lott’s house, the location depicted in Constable’s The Hay Wain.

Sledge in gallery

Sledge in gallery

Yet there is a further significance in his decision to make a sledge from frames. In his Critique of Judgement, Immanuel Kant argues that picture frames and plinths are parerga, material objects that function as borders demarcating the artwork as such from the surrounding non-art environment (or one might say: frames divide the “aesthetic” from the “non-aesthetic”). Insofar as they perform this function, frames are ostensibly incidental to the artwork they contain. And yet, as Jacques Derrida contends in The Truth in Painting frames both define the art as art and its immediate environs as environs; to that extent, frames are conceptually internal to the artwork. Lest this sound overly abstract, procedures of framing and exposing/analysing the framing mechanisms undertaken in varying degrees throughout the artworld are recurrent features of Institutional Critique artistic practice. It would be inaccurate to state that Dobrowolski’s practice is Institutional Critique tout court; one might nonetheless detect a shared sensibility: a certain need to distance themselves from and yet also be implicated in the artworld through acts of (re-)framing and being framed. The frame-sledge serves a striking metaphor for Dobrowolski’s complex detachment from the artworld and his continuity with it.

Toy action man dogs and full size sledge. Photo-Fergal Buckley.

Toy action man dogs and full size sledge. Photo-Fergal Buckley.

As with the frame-sledge, Dobrowolski’s photographs play with the actuality of life in Antarctica in ways that nostalgically re-mythologize the courageous explorers who tried to chart this inhospitable region as well as its contemporary occupants. A youthful fascination with the outer reaches of civilization—distant geographical locations that suggest the possibility of adventure—is communicated by various strategies. Illustrated children’s books, for instance, are photographed opened to a page depicting a polar vehicle juxtaposed with a real-life version in the background. In other photographs, Dobrowolski places toys in the Antarctic landscape: on some occasions he carefully uses perspective and the distance between foreground and background to suggest humorously that the toy is of equal stature to its authentic counterpart; on others there is no such artifice, thus leading to the striking size-based contrast between toy figure and worker to be completely obvious—while, nonetheless, inviting one to perceive imaginatively these toy figures as denizens of Lilliput who have travelled to Antarctica and now work alongside humans. The photographs aren’t so much mythological because they reflect Antarctic life but rather because they manufacture expectations of what that life consists of. Another photograph shows—again using a perspective trick—pretend toy dogs “pulling” the frame-sledge. From various historical, media, and literary sources the depicted scene looks plausible—it conforms to our expectations—and yet the scene is incorrect: dogs haven’t been in Antarctica since early 1994. Nonetheless, although the frame-sledge was towed by skidoos, its handlebars indicate that this design was “intended” to be pulled by dogs.

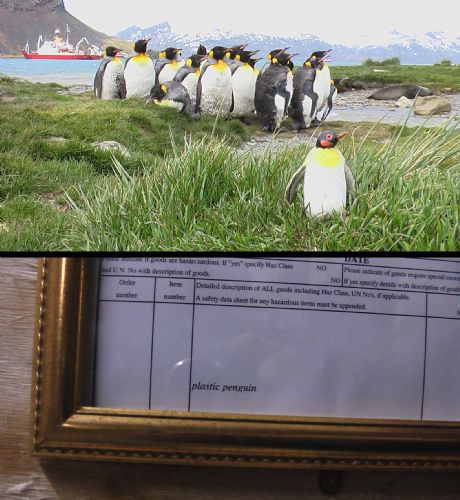

TOP: Plastic penguin and real penguins. BOTTOM-detail of bill of lading document in gold frame on box

TOP: Plastic penguin and real penguins. BOTTOM-detail of bill of lading document in gold frame on box

The mythologization heads in various directions simultaneously. In addition to the photographs, Dobrowolski has appropriated BAS wooden storage boxes and has placed within them the toy figures he took to the Antarctic. Some of the photographs are used in the boxes. The inner surfaces of the boxes are adapted so that they become snowy landscape, blue skies—backdrops for the toy figures arranged as if living and working in Antarctica. The boxes, then, no longer serve as containers but become frames that provide narrative coherence for the scenes visualized between its borders. Prior to becoming scenes, however, Dobrowolski used them to send back various items from Antarctica. Each packed box must have an official Bill of Lading (BOL) on it, a record that details precisely what the box contains. As these serve as additional evidence of his time in Antarctica, he has framed and placed them onto the exterior of each box. One of these reads “rejection letters” and adds the further piece of info: “ashes.” Bringing storage boxes into the gallery changes them from mundane functional items useful to those working in Antarctica into near-fetish objects betokening another culture. Similarly, the discarded frames travel to Antarctica and become components of an artwork; while the toys are photographed in situ and are transformed into scenes. The negotiation of geographic and other types of distance, as well as the transition between social and institutional contexts significantly and quasi-magically confers a new status upon these materials, elevating them into something greater or more dramatic than they might commonly be taken for.

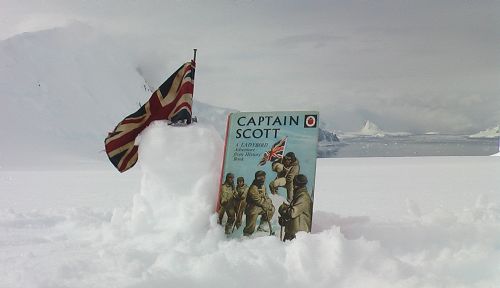

Ladybird book in the Antarctic

Ladybird book in the Antarctic

If there is a play of mythologization in Dobrowolski’s work, then it should be noted that this play doesn’t aim to engender an illusionary image of Antarctica but instead reflects the genuine heroism of those who tried to chart this continent. Built into Dobrowolski’s works is the awareness of risk and failure that has largely characterized Antarctic exploration. One photograph depicts the front cover of an illustrated children’s book. Upon the cover there’s a drawn picture of Captain Scott plunging the Union Flag into the white ground. And yet, the intended heroism of this cover is undercut by Dobrowolski who photographs the book adjacent to a small flag—placed there by himself—which is half-buried in cold snow. In this way we are reminded that Scott’s bravery and patriotism was ultimately the cause of his downfallThe reality of the Antarctic seeps into Dobrowolski’s artwork through other routes, too. It’s relevant, for example, that stencilled onto the side of the storage wooden boxes is lettering that identifies them as the property of the BAS. Photographs operate as documentary “evidence” despite the artificialness of the composed toy scenes. Mythologization and reality aren’t polarized oppositions in Dobrowolski’s Antarctic works; instead, the former term derives from and even produces the latter. Antarctica is elsewhere, but the sledge, boxes, and photographs bring it to our locale. Antarctica starts here, too.

Painting in sledge food box in gallery

Painting in sledge food box in gallery

Intermixed with the genuine playfulness and humour of Dobrowolski’s work are levels of complexity that I can only point to here in closing this essay. Essentially, each item of Dobrowolski’s oeuvre functions simultaneously as an independent stand-alone work and as being a point that is continuous with and refers to a wider constellation. The frame-sledge is rearticulated through the storage boxes that mesh together the photographs he has taken during his time in Antarctica, the BOLs that record each box’s contents on the journey home, fragments of frames positioned within the boxes, and the lecture-performance given by Dobrowolski that has become such a key facet of his practice. Each work seems restless, dynamic, never occupying a fixed position but shuttling between itself and the other works. And just as the gallery becomes a frame for these works, it’s nonetheless evident that the works will partially escape the gallery, and the artworld, inasmuch as they always appear to belong elsewhere—in the reality and mythology of Antarctica