Introduction

I have known and admired Chris Dobrowolski's work for several years and was delighted to be asked to contribute to this catalogue. The initial idea was that I might write an introductory essay. I suggested that an interview with the artist might be an appropriate format and so we met and recorded a three hour conversation. Very early on in the discussion I remembered that Chris Dobrowolski has the habit of breaking into long, animated and very funny anecdotes which leave little space for analytical contributions from others and do not lend themselves to a text which follows a regular interview format. We agreed, therefore, that rather than simulate a conversational exchange, the text should consist of a montage of statements from both of us structured around the chronology of the exhibition. One reason for this being an appropriate approach is that Dobrowolski, who I regard as a very serious, and significant, artist is also one that is reluctant to be caught appearing to talk seriously about his work. This paradox exists within a practice full of pregnant contradictions. The word 'paradox' is one of the few overtly serious words that he consistently uses about his work. I say that he is reluctant to appear to talk seriously because I believe that his humorous monologues, delivered at the slightest provocation, are actually serious illuminations of his work and inseparable from it. (He is, in fact, in some demand giving slide-talks which are extensive versions of these monologues based around his work. Recently he was invited to Japan for the purpose). He has a strong sense of the ridiculous but, at the same time, the work might be too serious for him to talk seriously about. The extent to which he is conscious of this he does not betray. That would be to talk seriously...

None of this is to imply affectation. On the contrary, one of the great strengths of his work is its integrity; its lack of artifice. One of the many contradictions inherent in his practice to date is that he has produced works of art through processes of making that have resisted the whole idea of art and its trappings. This retrospective exhibition, largely undertaken, he says, 'To test what it is I've been so adamant that I hate', represents a point in a journey towards an increasing preparedness to take the possibility of 'art' seriously. 'Progress from being an anti-artist to an artist has been slow, he explains. The things I make have become more self-conscious."

He remains uncertain and I, for one, hope that he retains some doubt. His ambivalence is rooted in a recognition that what we call 'art' exists in particular ways of relating to objects - ways of attending to them and ways of situating them socially. Being both art and not art his work has the capacity to engage interests which currently fall outside notions of 'art', as well as rewarding the kinds of scrutiny associated with the gallery. It is in the multiplicity of roles and meanings that objects can perform for different people that art can be part of lives, marking rites of passage, events and relationships, for example. The recognition of the importance of such 'extra aesthetic' functions is slowly beginning to return in an art world which, in the wake of modernism, still largely treats them as irrelevant.

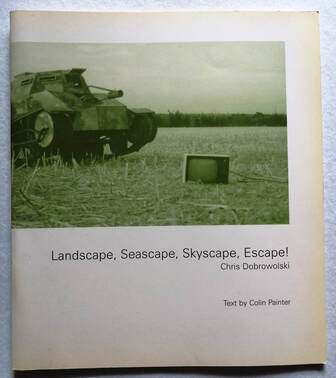

The exhibition is structured around six pieces made over the last ten years. Each is a kind of 'vehicle' - a term with a rich variety of resonances. As modes of physical transport they all 'work' and, with the exception of the aeroplane, have all been 'driven' by the artist. Dobrowolski's escapades in these eccentric vehicles - are inseparable from his relationship to them. He offers some clues to the richness of this in the exhibition through the presence of related photographs, models and smaller works that he thinks of as 'sketches'. His words in this catalogue also provide insights.

I have said that all of these vehicles 'work' but if they really did work with twenty-first century efficiency they would not invite us to attend to them as 'art'. We would see them as cars, hovercraft, tanks and aeroplanes. It is their manifest absurdity as realistic modes of transport that invites, and rewards, a contemplative attention beyond the necessities of practicality. In tension with humour there is a profound futility inherent in the limitations of these vehicles and the artist's propositions of 'escape' in them - probably the most powerful paradox of them all.

Dobrowolski's obsessive fabrication is a genuine extension of boyhood model-making and go-kart construction with pram wheels and wooden boxes. The extension of go-kart manufacture into the terrain of art has profound consequences. It is important to the artist that nothing is done for effect. The facture and finish is determined by the demands of function. Little is offered that is not shaped by practical necessities. But this is no innocent un-reflexive endeavour. A fine art graduate of the Royal College of Art, he is aware of the context and traditions within which his work will be given meaning as art. It is an awareness that contrasts with his modest social background strongly influenced by a Polish immigrant father. The pretentions and mystification often associated with art - still far from disconnected from the furniture of social class - are probably largely responsible for his sense of the ridiculous as well as his reluctance to collaborate unreservedly. His persistence in street-level boyhood craft activities can be seen as, in itself, a denial of what he has seen as the affectedness of the art world. At the same time, in yet another paradox, his modes of transport often speak of a world of upper class eccentricity.

There is something here of Alan Bennett's observations that as a child what he read in books never quite accorded with his own experience of a lowly urban upbringing. "...thatched cottages, millstreams, where the children had adventures, saved lives, caught villains ... before coming home... to eat sumptuous teas off chequered tablecloths in low beamed parlours... In an effort to bring this fabulous world closer to my own threadbare existence, I tried as a first step substituting' Mummy' and 'Daddy' for my usual 'Mam' and 'Dad' but was pretty sharply discouraged. My father was hot on anything smacking of social pretention..." (Alan Bennett, The Treachery of Books).

If the approved templates, through which we are invited to construe reality as children, do not work for us it inevitably affects our attitudes towards them when, as adults, we come to see them for what they are. From that perspective some of Dobrowolski's allusions to upper class eccentricities in his adult extension of go-kart production are not without satire. No three-wheeler of Del and Rodney Trotter fame but a pedal car more resonant of Wooster and Jeeves...

The following texts follow the framework of the exhibition, addressing each of the six major pieces sequentially. It is hoped that it provides some sort of handle on the artist's intentions and ways of working - at the same time, perhaps, offering some response to the work in relation to which visitors might hone their own perceptions.

None of this is to imply affectation. On the contrary, one of the great strengths of his work is its integrity; its lack of artifice. One of the many contradictions inherent in his practice to date is that he has produced works of art through processes of making that have resisted the whole idea of art and its trappings. This retrospective exhibition, largely undertaken, he says, 'To test what it is I've been so adamant that I hate', represents a point in a journey towards an increasing preparedness to take the possibility of 'art' seriously. 'Progress from being an anti-artist to an artist has been slow, he explains. The things I make have become more self-conscious."

He remains uncertain and I, for one, hope that he retains some doubt. His ambivalence is rooted in a recognition that what we call 'art' exists in particular ways of relating to objects - ways of attending to them and ways of situating them socially. Being both art and not art his work has the capacity to engage interests which currently fall outside notions of 'art', as well as rewarding the kinds of scrutiny associated with the gallery. It is in the multiplicity of roles and meanings that objects can perform for different people that art can be part of lives, marking rites of passage, events and relationships, for example. The recognition of the importance of such 'extra aesthetic' functions is slowly beginning to return in an art world which, in the wake of modernism, still largely treats them as irrelevant.

The exhibition is structured around six pieces made over the last ten years. Each is a kind of 'vehicle' - a term with a rich variety of resonances. As modes of physical transport they all 'work' and, with the exception of the aeroplane, have all been 'driven' by the artist. Dobrowolski's escapades in these eccentric vehicles - are inseparable from his relationship to them. He offers some clues to the richness of this in the exhibition through the presence of related photographs, models and smaller works that he thinks of as 'sketches'. His words in this catalogue also provide insights.

I have said that all of these vehicles 'work' but if they really did work with twenty-first century efficiency they would not invite us to attend to them as 'art'. We would see them as cars, hovercraft, tanks and aeroplanes. It is their manifest absurdity as realistic modes of transport that invites, and rewards, a contemplative attention beyond the necessities of practicality. In tension with humour there is a profound futility inherent in the limitations of these vehicles and the artist's propositions of 'escape' in them - probably the most powerful paradox of them all.

Dobrowolski's obsessive fabrication is a genuine extension of boyhood model-making and go-kart construction with pram wheels and wooden boxes. The extension of go-kart manufacture into the terrain of art has profound consequences. It is important to the artist that nothing is done for effect. The facture and finish is determined by the demands of function. Little is offered that is not shaped by practical necessities. But this is no innocent un-reflexive endeavour. A fine art graduate of the Royal College of Art, he is aware of the context and traditions within which his work will be given meaning as art. It is an awareness that contrasts with his modest social background strongly influenced by a Polish immigrant father. The pretentions and mystification often associated with art - still far from disconnected from the furniture of social class - are probably largely responsible for his sense of the ridiculous as well as his reluctance to collaborate unreservedly. His persistence in street-level boyhood craft activities can be seen as, in itself, a denial of what he has seen as the affectedness of the art world. At the same time, in yet another paradox, his modes of transport often speak of a world of upper class eccentricity.

There is something here of Alan Bennett's observations that as a child what he read in books never quite accorded with his own experience of a lowly urban upbringing. "...thatched cottages, millstreams, where the children had adventures, saved lives, caught villains ... before coming home... to eat sumptuous teas off chequered tablecloths in low beamed parlours... In an effort to bring this fabulous world closer to my own threadbare existence, I tried as a first step substituting' Mummy' and 'Daddy' for my usual 'Mam' and 'Dad' but was pretty sharply discouraged. My father was hot on anything smacking of social pretention..." (Alan Bennett, The Treachery of Books).

If the approved templates, through which we are invited to construe reality as children, do not work for us it inevitably affects our attitudes towards them when, as adults, we come to see them for what they are. From that perspective some of Dobrowolski's allusions to upper class eccentricities in his adult extension of go-kart production are not without satire. No three-wheeler of Del and Rodney Trotter fame but a pedal car more resonant of Wooster and Jeeves...

The following texts follow the framework of the exhibition, addressing each of the six major pieces sequentially. It is hoped that it provides some sort of handle on the artist's intentions and ways of working - at the same time, perhaps, offering some response to the work in relation to which visitors might hone their own perceptions.